Decide How to Decide: Empowering Product Ownership

As the product owner, you are responsible for the product’s vision, and ultimately, the value of your product. You “own” the backlog. If your responsibilities include upstream product management—what I refer to as strategic product ownership—then you also shepherd your product through its entire lifecycle.

Bottom line, your prime responsibility is deciding what to build and when to build it. Your decisions guide not just the health and well being of your product, but also all the people engaged in product discovery and delivery.

Yet a common product ownership struggle I see in agile teams—regardless of industry and product type—is determining how to make decisions. As an agile coach, I use a pattern I call “Decide How to Decide.” It’s a simple technique to help people make transparent, participatory, and trusted decisions.

Start with Your Decision Rule.

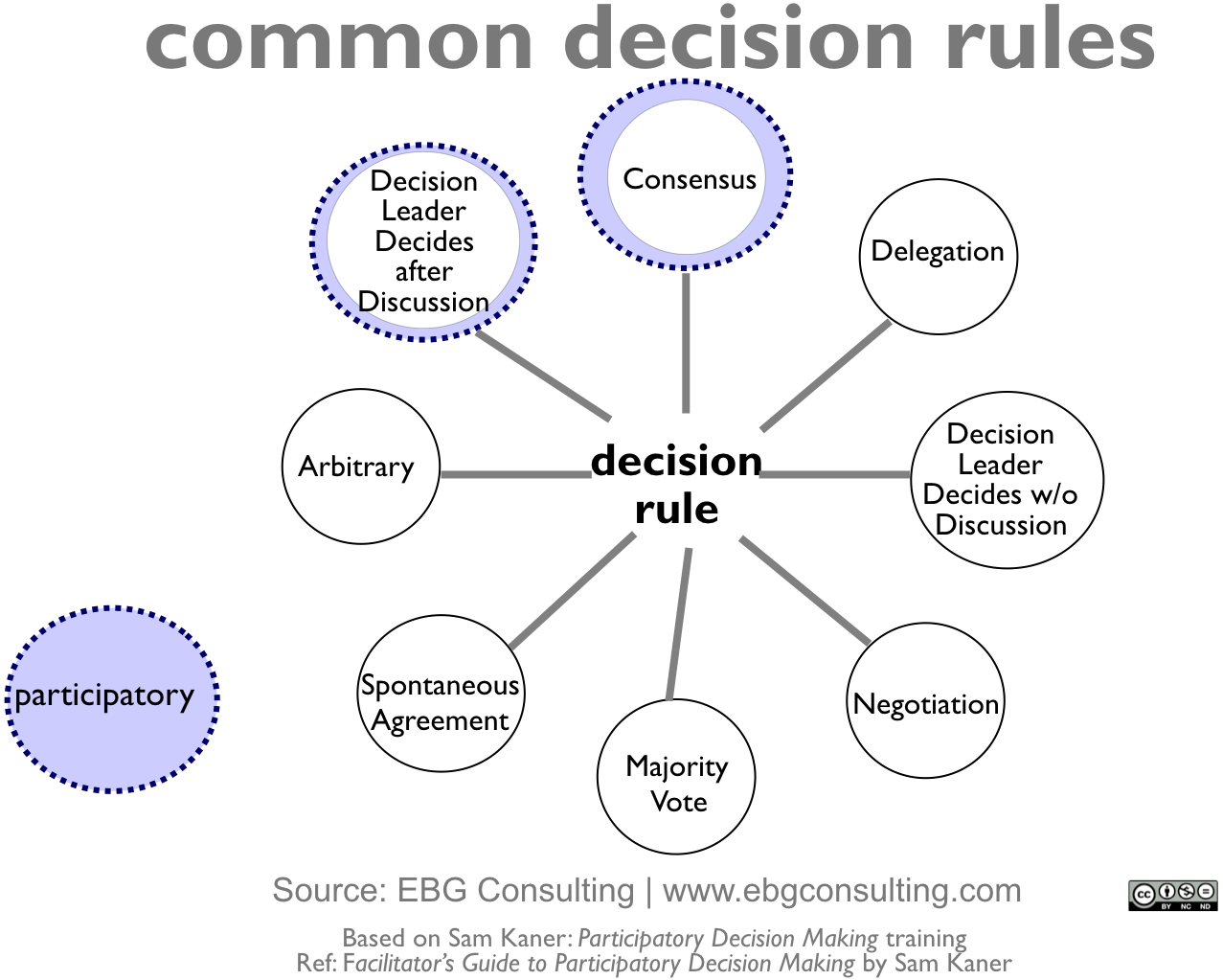

A decision rule is a mechanism to reach closure. It communicates to everyone how—and when—a decision has been made. Here are several common decision rules.

Notice the two rules categorized as “participatory,” Decision Leader Decides after Discussion and Consensus. These are ideal for agile teams. They engage stakeholders and typically result in decisions that are more sustainable. You need that type of buy-in for the high stakes decisions you make all the time as part of agile product planning and analysis. My work with agile teams shows, again and again: using a transparent, participatory decision-making process helps everyone—not just you, the product owner.

But be careful! Many agile teams have a misconception about consensus. Consensus is a form of agreement in which everyone is of “one mind”. Sure, some decisions are best made by consensus, for example, a decision on the time and location for your team’s daily standup.

However, product decisions rest firmly with you, the product owner. Decisions about backlog refining, planning and validation—what goes in, what comes out, what the optimal sequence is, which items will be pulled for the next delivery cycle, what metrics you’ll use to validate your delivery choices, and so on—these decisions need to be made by you, the product owner—after discussion with your product partners.

Making Decisions

The first step is clearly defining what needs to be decided and sharing it with the appropriate participants. These participants are typically a mix of product partners from the business, technology and customer communities. Since your product partners have deep and broad product knowledge, and often care passionately about the product, you need to find out where they stand on the decision before you finalize it.

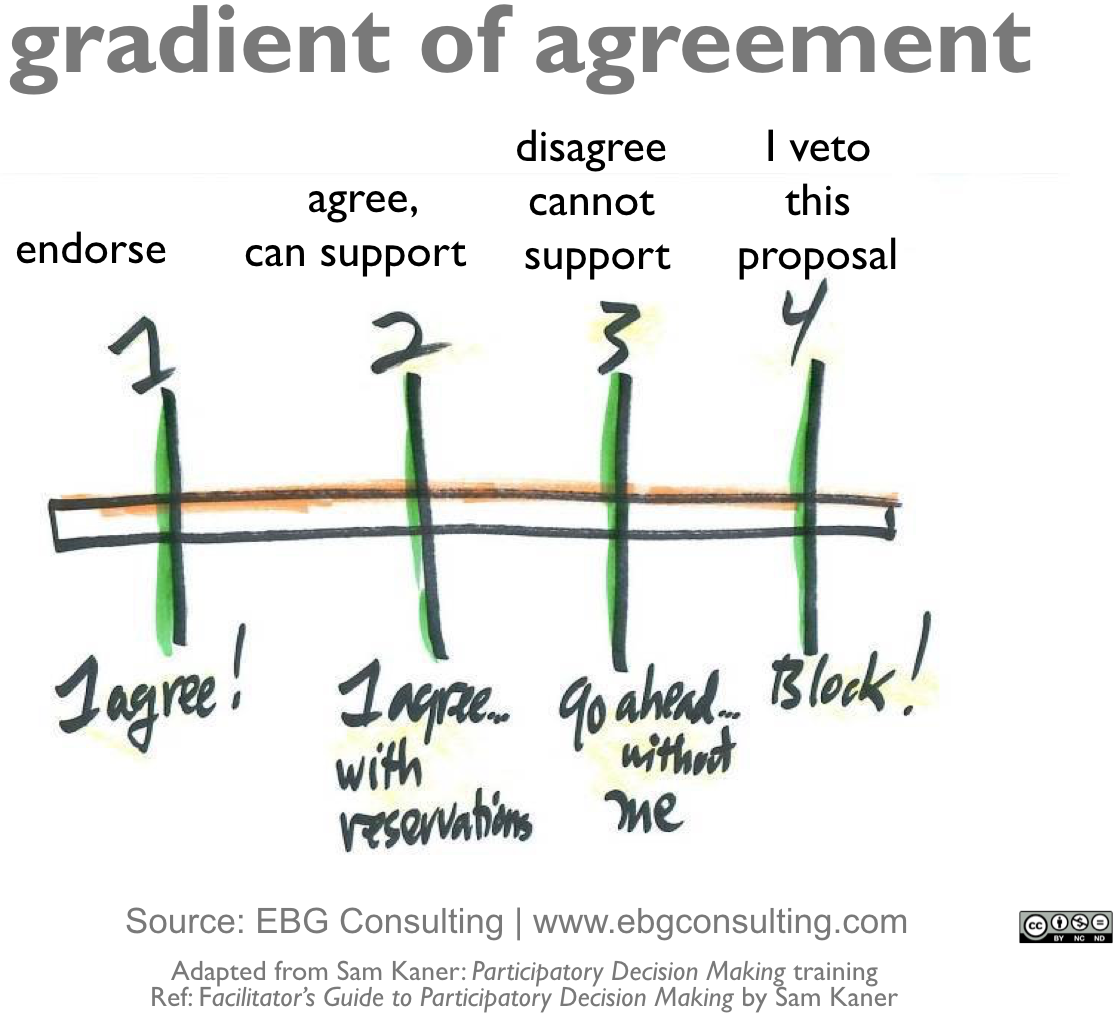

A tool I use is the gradient of agreement (see below). It goes beyond a simple yea or nay, using a scale of four levels of agreement. This continuum helps people express their degree of accord with the proposed decision quickly and efficiently.

For the proposed decision, ask the participants where they stand along the gradient of agreement. You ideally want people to be in “the zone of agreement” (“1’s and “2’s). When there are any “3’s” or “4’s”, pause. Ask for background on why those not in the zone of agreement can’t support the decision as-is, or are vetoing it. Their perspectives may provide new insights about the proposal and lead to possible adjustments. If you do adjust the proposed decision, repeat the polling. In my experience, most teams reach agreement in one or two iterations of proposal generation, narrowing, and checking for agreement.

Consider Not Owning Every Product Decision

There are situations where it may be wise to assign decision-making authority to someone else. (You do, however, need to decide how to decide and be explicit about who is the decision leader). Take, for example, a decision about technical architecture. Unless you have deep technical expertise, it’s wise to have a lead architect be the decision leader.

Just because you might choose not to own that final decision, doesn’t mean you aren’t engaged in decision-making. “Decision Leader Decides after Discussion” is a participatory decision rule. This means the right people need to be consulted—including of course, you! Your knowledge about product strategy, customer problems, market risks, competitive intelligence, and more, are crucial to making a solid technical architecture decision.

Case in point: I recently worked a delivery team that on their own made a decision about the product’s technical architecture. They were unaware of regulatory changes on the horizon that would have significantly influenced their choice. In retrospect, discussing the choice with the product owner, prior to making a decision, could have prevented an unfortunate and costly mistake.

The Value of Transparent Decision-Making

The act of explicitly deciding how to decide has a powerful effect on agile teams. It promotes accountability and empowerment. It proactively incorporates seeking input and expertise to deliver the best product possible. The bonus—it concurrently builds trust and transparency.

How do you decide how to decide? Share your thoughts, below.

Sign up here to join our growing product, business analysis and project community. You’ll get periodic tips for effective agile product discovery and delivery on topics like collaboration, discovering product requirements, facilitating analysis and planning valuing and slicing product needs, validating product decisions, and more.

Totally agree on decision making, and follow through on decisions. However, I use the Fist of Five for consistency, where 5 is total agreement, 3 is can live with it, and 1 is a big blocker.

I also suggest that in some organizations, follow through on decisions is an even bigger problem than deciding. Using the some visible management tool for decisions can be helpful in those cases so that those decisions don’t have to be made over and over in subsequent meetings where participants try to recall what was said before.

Hi Karen: sounds good. I like the gradient of four, as it gets people to be clearer vs the ‘middle’. whichever one choices, the key is to have decision making ‘rules’ transparent and consistently use them, checking for agreement.

BTW: the original gradient of agreement, predating the Fist of Five (via janet danforth and then jean tabaka) is from Sam Kaner. I first learned it from Sam via a training and after maaaany years of using it and adapting it, i found the gradient of four worked best.

[…] effectiveness and efficiency. It all comes down to healthy, collaborative conversations based on clear decision rules and processes. [5] Be sure you share your decision factors and decsion rules as you collaborate to discover and […]

I can’t see one very powerful rule I use : consent. No “real” objection ? Then give us your explicit consent, so that the group can move forward.

Hello Marianne,

Happy, HEALTHY new year to you, and yours.

Thanks for writing.

I’m glad to see you are having a good experience with decision-making.

In the model I use and describe in this blog, we check-in for agreement using the Gradient of Agreement. This is how we very explicitly check for consent.

Each person shares where they stand with regard to the Gradient of Agreement. Anyone with an objection or reservation (i.e., they do not ‘consent’), indicates this with a “2”, “3”, or “4” (versus a “1”). Next, any person, not a “1”, is then asked to share their reservation, concern, or objection. In that way, she or he gives voice to their issue with the proposed decision.

As I am assuming you intend and use “consent”, the framework and process I use and describe aligns with your use of consent decision-making.

I hope this clarifies your comment.

~ ellen